Prices incl. VAT, free shipping worldwide

Ready to ship today,

Delivery time appr. 3-6 workdays

Product description

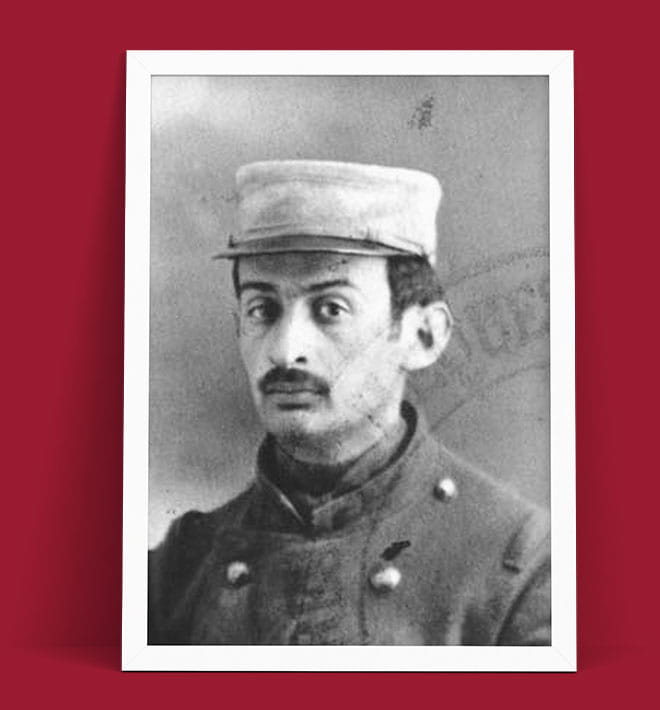

"Bronze Relief - Portrait of the Father (1912) - Otto Gutfreund"

| Height | 38 cm |

| Width | 28 cm |

| Length | 3 cm |

| Weight | 3,2 kg |

Bronze Relief - Portrait of the Father (1912) - Signed Otto Gutfreund

A striking synthesis of emotional depth and formal abstraction, Otto Gutfreund’s “Portrait of the Father” (1912) stands as a seminal example of early cubism sculpture. This bronze relief, limited to just 20 casts, represents a rare and highly significant creation in the evolution of modern sculpture. Gutfreund’s remarkable treatment of form and surface communicates a psychological intensity while adhering to the experimental principles of Cubism, a movement still in its radical infancy at the time. Signed by the artist himself, this work is not only a deeply personal homage to his father but also a groundbreaking contribution to twentieth-century sculptural innovation.

The Bohemian Prodigy and His Artistic Awakening

Otto Gutfreund was born on August 3, 1889, in Dvůr Králové nad Labem, a small town in the then Kingdom of Bohemia, today part of the Czech Republic. A man of diverse talents and formidable intellect, Gutfreund began his formal education at the School of Ceramics in Bechyně before advancing to the School of Applied Arts in Prague. His formative years laid the foundation for his intense fascination with form, structure, and materiality. By the time he arrived in Paris in 1910 to study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière under Antoine Bourdelle, the intellectual climate of avant-garde Europe had already begun to shape his artistic identity. It was in Paris that he encountered the works of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and other pioneers of the cubism sculpture movement, a discovery that would drastically influence his sculptural language.

The Emergence of Cubist Principles in Bronze

Gutfreund’s Portrait of the Father was conceived and executed in 1912 in Paris, the pulsating heart of modernist experimentation. At the time, Gutfreund was absorbing the fractured geometries and philosophical rigor of the Cubist aesthetic, applying it not only to pictorial art but to sculpture — an act of considerable boldness and originality. This bronze relief exemplifies how cubism sculpture redefined the relationship between volume and space. The depiction of his father’s face is not idealized or sentimental; instead, it is rendered through angular planes, abrupt transitions, and a tension between mass and void that speaks directly to the innovations of early Cubism. This is not merely a portrait but a sculptural manifestation of emotional complexity translated into cubist syntax.

Psychological Depth Encased in Abstract Form

Unlike the serene classical busts of traditional portraiture, Gutfreund’s relief plunges the viewer into a densely folded matrix of planes and shadows. The father's head appears both confined within and emerging from the solid bronze block, suggesting the inescapability of time, memory, and familial presence. Each furrowed line and sharply demarcated edge tells of a life weathered by experience. The mouth, subtly open, evokes speech halted or emotion withheld, while the eye sockets, shadowed and sunken, suggest introspection, perhaps sorrow. The genius of this cubism sculpture lies in its ability to convey not just physical likeness but psychological resonance through abstract means. In doing so, Gutfreund pushed sculpture into new expressive territory.

A Sculpture Born of Conflict and Transition

1912 was not only a year of intense artistic innovation for Gutfreund but also a period of personal introspection. Creating Portrait of the Father was an intimate act, developed far from his Bohemian homeland, at a time when he was surrounded by radical ideas in the Parisian avant-garde. The choice of bronze — a traditional and enduring material — juxtaposed with the experimental cubist form, further enhances the sculpture’s tension between continuity and disruption. Gutfreund’s technique, applying heavy modeling with almost brutal force, accentuates the relief’s raw vitality. Rather than polishing the bronze to elegance, he retained the roughness of touch, allowing the material itself to speak of struggle and gravitas — hallmarks of his cubism sculpture.

Legacy of a Limited Edition

Only 20 casts of Portrait of the Father were ever produced, each one bearing the direct signature of Otto Gutfreund. These bronzes were not created for mass admiration but rather as personal, almost sacred objects, distributed with the utmost discretion. As a result, each piece carries an intimate provenance and occupies a crucial place in the lineage of modern sculpture. Collectors and institutions that own one of these rare works possess not just a relic of modernist history, but a profoundly personal statement from an artist who bridged the emotional intensity of Expressionism with the formal rigor of Cubism.

Gutfreund’s Lasting Impact on Cubist Sculpture

Though Gutfreund’s life was tragically cut short in 1927, his contributions to modern sculpture remain deeply influential. He was one of the first artists to fully integrate the principles of Cubism into three-dimensional form, predating even Jacques Lipchitz in the maturity of his sculptural vision. After returning to Prague in 1918, Gutfreund became a leading figure in Czech modernism and a professor at the Prague Academy of Arts, where he continued to shape generations of sculptors. His early Paris works, especially Portrait of the Father, remain touchstones in the history of cubism sculpture, marking a moment when form, emotion, and theory converged with exceptional clarity.

A Testament in Bronze to Modernism’s Inner Struggle

In Portrait of the Father, Gutfreund gives us more than just a family remembrance; he gives us a sculptural essay on the modern condition. The work’s solidity anchors it in tradition, yet its radical formal language propels it into the avant-garde. Its cubist fracture is not a rejection of the human form, but a deepening of its potential for meaning. It is precisely this tension — between the personal and the universal, the traditional and the experimental — that makes Portrait of the Father a masterwork of cubism sculpture. It is a silent, enduring voice in bronze, echoing across time and reshaping the very notion of what sculpture can be.

Our advantages

free shipping

Worldwide free shipping

14 days money back

You can cancel your order

within 14 days

secure payment services

Paypal, Master Card, Visa, American Express and more